Of all the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World only the pyramids of Giza remain. Composed of millions of limestone blocks weighing anywhere from 2.5 to 15 tons perhaps the most amazing thing about the pyramids is not their size or longevity but the fact that they were constructed without any form of advanced moving or lifting technology.

Today, however, we have heavy equipment of all sizes and configurations to handle earth moving and other construction chores and because of this we are able to dig deeper, build higher and build faster and better than the ancient Egyptians themselves ever imagined. But how did we get to this point? What are the origins of today’s heavy equipment and what does the future hold? Below we’re going to take an in-depth look at those questions.

Table of Content

Forebears

While we can rightfully marvel at what the ancient Egyptians did with simple rollers and elbow grease none of the technology used to build the pyramids actually spawned any of today’s heavy equipment. To find the mechanisms that led to today’s front end loaders, cranes, combine harvesters, landfill compactors and more we have to look to the people whose influence can still be felt today in nearly every facet of society: the Romans.

Besides inventing concrete and the arch the Romans also laid the foundation for many types of contemporary heavy equipment that would go on to play pivotal roles in both agriculture and construction. Chief among these was the crane. (While some theorize that the Egyptians used a type of small-scale lifting device on the pyramids there is no actual proof of that.) Some Roman cranes were as tall as a three story building and, although human or animal powered, could lift several tons of material at one time. As recently as the Middle Ages the Roman crane model was still in use and essentially unchanged.

Into the Modern Age

Right up into the 19th century equipment used to build roads, bridges and buildings and to enable agriculture was all powered by either man or beast. Even the Brooklyn Bridge – long considered a benchmark heralding the arrival of a new technological age – was largely built by hand. Men were sent down into the caissons under the growing towers of the bridge to excavate the river bottom with pick axes and shovels. Compressed air was pumped into the caissons to keep the East River at bay, though its use resulted in many men succumbing to “the bends”, or nitrogen bubbles in their blood from rapid decompression. It wasn’t until the late 19th century that steam engines were finally applied to construction equipment and liberated it once and for all from the muscle. And when it did all bets were off as far as what was possible.

The Panama Canal is perhaps the earliest and best example of the profound effect steam power had on the construction industry. Nearly all of the 78,000,000 cubic yards of material removed along the length of the canal was scooped up by steam shovels and dumped into open railroad cars that were then pulled away by steam locomotives.

On the agricultural front Benjamin Holt’s steam powered combine harvester transformed farming and, for better or worse, laid the foundation for today’s multi-billion dollar agribusinesses. In 1892 the French invented the gasoline powered tractor, an innovation that quickly jumped the Atlantic Ocean and caught the eye of Holt who produced his own version which in short order became staple equipment on American farms large and small.

The 20th Century:

Heavy Equipment Gets Serious

Right up into the 19th century equipment used to build roads, bridges and buildings and to enable agriculture was all powered by either man or beast. Even the Brooklyn Bridge – long considered a benchmark heralding the arrival of a new technological age – was largely built by hand. Men were sent down into the caissons under the growing towers of the bridge to excavate the river bottom with pick axes and shovels. Compressed air was pumped into the caissons to keep the East River at bay, though its use resulted in many men succumbing to “the bends”, or nitrogen bubbles in their blood from rapid decompression. It wasn’t until the late 19th century that steam engines were finally applied to construction equipment and liberated it once and for all from the muscle. And when it did all bets were off as far as what was possible.

The Panama Canal is perhaps the earliest and best example of the profound effect steam power had on the construction industry. Nearly all of the 78,000,000 cubic yards of material removed along the length of the canal was scooped up by steam shovels and dumped into open railroad cars that were then pulled away by steam locomotives.

On the agricultural front Benjamin Holt’s steam powered combine harvester transformed farming and, for better or worse, laid the foundation for today’s multi-billion dollar agribusinesses. In 1892 the French invented the gasoline powered tractor, an innovation that quickly jumped the Atlantic Ocean and caught the eye of Holt who produced his own version which in short order became staple equipment on American farms large and small.

The 1920s:

Innovation and Impact

During the 1920s bucket wheel excavators began appearing in mines where they transformed the landscape and turned mining from a specialty business into true heavy industry. On roads and construction sites the changes were just as dramatic. Within a decade after the end of the war gas powered front end loaders, excavators and backhoes all made their appearance and fuelled the building boom of the 1920s that transformed the modern cityscape and gave rise the skyscraper. The effects of the new heavy equipment were also felt underground where subways tunnels became cheaper and faster to dig. The Holland Tunnel in New York City became the longest underwater tunnel in the world when it opened in 1927.

The 1930s: Helping Society Stay Afloat

The stock market crash of 1929 pulled the rug out from under the global economy which had been in overdrive for nearly a decade. The Great Depression that followed saw 25% unemployment and widespread despair. It’s fair to say however that heavy equipment, and especially excavators large and small, played an important role in keeping the American economy from complete collapse. That’s because a series of large, high profile infrastructure projects we initiated that put tens of thousands of people back to work. Those projects included Hoover Dam, both the Lincoln and the Midtown Tunnels in New York City, the Grand Coulee Dam in Washington state, the Overseas Highway that ran through the Florida Keys, the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco and LaGuardia Airport in New York. All of these projects and more were made possible by the heavy equipment of the time and served to keep the economy going when private sector jobs were hard to come by.

The Post-war Era

While advances in heavy equipment during the early part of the 20th century helped reshape America and prevent total economic collapse it was really in the aftermath of World War II that heavy equipment as we know it today came into being. With large swaths of Europe and Asia in ruins and the United States basically unscathed America emerged from the bloodbath as the economic engine that would fuel global post-war recovery. American exports flooded into markets overseas and the new wealth being created at home lit a fire under the construction industry. Everyone wanted their own house in the new suburbs and the Eisenhower Interstate Highway System would let them commute from there to their job in the city centre quickly and easily. More on that in a moment.

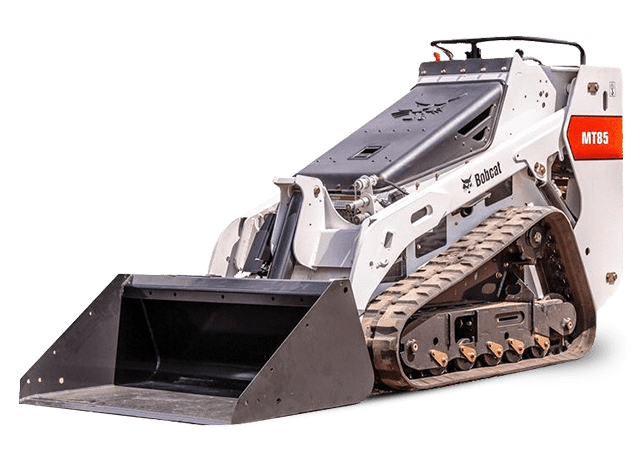

One of the biggest innovations that came about at this time was the invention of the skid steer loader. In 1957 the brothers Cyril and Louis Keller invented a machine to help a friend of theirs clear away turkey droppings on his farm. This machine had a single caster wheel at the rear that allowed it to turn in place, which gave it a distinct advantage in tight spots over other equipment. The brothers were bought out the following year by the Melroe Manufacturing Company who kept the Keller brothers on and tasked them with refining their invention. In 1960 they came up with the idea of replacing the rear caster with an axle and two wheels and to make the wheels on one side run in opposition to the wheels on the other. The skid steer loader was born.

“Many historians point to the Federal Highway Act of 1956, which set the creation of the Eisenhower Interstate Highway system in motion, as the point when the heavy equipment industry as we know it today was officially born.”

The Spark That Set the Flame

Many historians point to the Federal Highway Act of 1956, which set the creation of the Eisenhower Interstate Highway system in motion, as the point when the heavy equipment industry as we know it today was officially born. The sheer magnitude of the project was daunting. Before all was said and done nearly 50,000 miles of multilane limited access highway was constructed at a cost estimated to be nearly half a trillion dollars in today’s money. If laid end to end the highways built for the system would circle the earth twice.

While construction companies from coast to coast rejoiced at the announcement of funding for the new system it quickly became apparent that there simply wasn’t enough heavy equipment in existence to actually build what the legislation called for. At the same time it also became apparent that building a six or eight lane freeway through the centre of a major metropolitan area was an entirely new ballgame and presented construction challenges never before encountered. Skid steer loaders that could operate in tighter urban environments became particularly important and demand soared. The 1960s also saw the development of the first mini excavators which – like the skid steer loader – allowed construction companies access to places full sized excavators simply couldn’t go. At the other end of the spectrum a new generation of so-called “monster machines” came online.

The new mega-machines included powerful motor-wheel scrapers that filled the need to handle the massive amounts of dirt that had to be moved in order to make the new roadways possible as well as larger, more powerful excavators, drillers and loaders. At any given time there were hundreds of such machines working on highway projects simultaneously in virtually all 50 states. Heavy equipment for mining also underwent a fundamental transformation during the decade with the development of 360 ton haul trucks, the largest shovel excavators ever made and the world’s largest dragline.

In the wake of the Arab Oil Embargo of 1973 many energy companies put their money into coal production as a bulwark against future oil shocks. This rush to coal meant that companies producing earthmoving equipment were suddenly overwhelmed with orders. So strong was demand that an order placed for a large excavator in 1973 might not be filled until 1976 or 77.

Filling the Parts Void

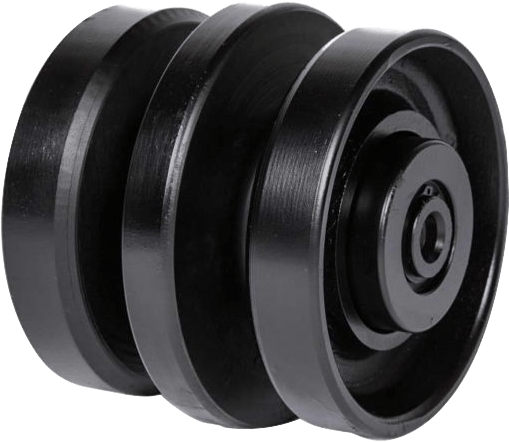

The proliferation of skid steer loaders, excavators of all sizes, dozers, scrapers, backhoes and more also raised the issue of parts. Even the hardiest heavy equipment would need servicing and replacement parts at some point. In addition, the widespread use of continuous track equipment brought with it a simultaneous spike in demand for replacement tracks, both steel and rubber. As a result, a number of companies such as Fortis that specialize in providing aftermarket parts for heavy equipment arose to meet this growing demand.

The Future of Heavy Equipment

The future of heavy equipment will see manufacturers focused on a number of issues including increasing the fuel efficiency of their equipment, reducing emissions and integrating new technologies to make the equipment both safer and more efficient. These changes are likely to manifest themselves in several ways including better, more efficient hydraulic systems, fuel injection and more advanced combustion systems. Also on the horizon are computer systems that will monitor all aspects of machine operation in real time and help conserve fuel and optimize performance.